HPSS: Rethinking Green Urbanism

Professors Anne Tate (ARCH) and Bryce DuBois (HPSS)

Comparative Utopias

Submitted: May 21, 2022

Edited for Portfolio: December 10, 2022

Two Tickets to Somewhere:

Professors Anne Tate (ARCH) and Bryce DuBois (HPSS)

Comparative Utopias

Submitted: May 21, 2022

Edited for Portfolio: December 10, 2022

Two Tickets to Somewhere:

Utopia Producers and Receivers in Ursula LeGuin’s “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” and “The Day Before the Revolution”

epigraphs

While you are looking, you might as well also listen, linger

and think about what you see.

–Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

The force of utopian thinking lies in its disinterested projection of places that are nowhere yet but already all around.

–Michael Sorkin, “Eutopia!”

![]()

![]()

![]()

and think about what you see.

–Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities

The force of utopian thinking lies in its disinterested projection of places that are nowhere yet but already all around.

–Michael Sorkin, “Eutopia!”

I read Ursula Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” some years ago and have been haunted by it ever since. Who can forget the image of the suffering child: “It could be a boy or a girl. It looks about six, but actually is nearly ten”—sitting in the corner of a small dark room, “in a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, or perhaps in the cellar of one of the spacious private homes”? The narrator of this story refrains from too prescriptive a setting, frequently offering the reader an imaginative choice, as in the above excerpt, that is, upon closer inspection, no choice at all, just a matter of design preference within the confines of this masterfully achieved city: “beautiful public building” or “spacious private home”? Either way, the reader’s position is not entirely unlike the citizens’ in this utopian vision where life is spatially and temporily thus spiritually prescribed.

There are seasonal festivals–the story opens with the “Festival of Summer’’ among ”great parks and public buildings,” a “great water-meadow called the Green Fields,” processions, music, and “decorous” unnamed people of all ages in the streets. “[T]hese were not simple folk, not dulcet shepherds, noble savages,” the narrator explains, precisions that preempt any attempt to dismiss Omelas as one of those “bland utopias.”

The narrator’s evocation of a “you” and a “we” throughout the text distinguishes LeGuin’s Omelas as a utopia that might very well be attainable, even if it appears to be a sort of “miracle.” Furthermore, it is eerily familiar to those who have been raised in the late 20th-century American suburban dream. “Let me tell you about the people of Omelas,” the narrator announces, “They were not naive and happy children –though their children were, in fact, happy. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched.”

In Omelas, the narrator adds, “I think there would be no cars or helicopters in and above the streets,” which the reader might interpret in two ways: first, that the technology of mechanical, fossil-fueled movement is somehow a sinister or un-utopian addition to city living and thus gladly banished here, and, second, that there is little crime in this urban vision to necessitate surveillance or policing power “in and above the streets,” an image that continues to plague certain neighborhoods of contemporary American cities. And yet, remarkably, the citizens of Omelas, the narrator imagines, “could perfectly well have central heating, subway trains, washing machines, and all kinds of marvelous devices not yet invented…fuelless power, a cure for the common cold.” All manner of technology is available to this city’s producers as it is to ours--the story projects itself into the present.

The clincher for the citizens of Omelas, however, as it is metaphorically also in ours, is the discovery that all of this “splendor” comes at a cost. At some point in their education, “between eight and twelve, whenever they seem capable of understanding,” each citizen must learn “that [the child] has to be there…that [the citizens’] happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.” Since there is much to gain (as the words in bold suggest) by accepting the suffering child, there is also much to lose.

Any effort to save the child is immediately abandoned by an additional stipulation, that this “splendor of their lives” will disappear if anyone attempts to save the child, and so the citizens of Omelas live knowing “that they, like the child, are not free.” The return on such a utilitarian investment–accepting the suffering of one for the happiness of thousands–will demand a lifetime of ignoring a hard reality. As Margaret Atwood writes in her dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale, “Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance. You have to work at it” (Reid, 2022). In Omelas, ignoring (in other words, not walking away) is what “makes possible the nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music, the profundity of their science.” These are not lazy people, and so their work and dedication are rewarded with “a sense of victory…the celebration of courage…[a] boundless and generous contentment…and the victory they celebrate is that of life.” Ignorance absent ignoring might very well achieve architecture, music, and science but without the many desireable qualifiers. If there is freedom for the citizens, it is only freedom from, as the narrator notes: “One thing I know there is none of in Omelas is guilt.”

Though some citizens are “content merely to know [the child] is there,” others choose to visit the child, “who has not always lived in the tool room and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice”: he sits in his excrement, thin, belly protruding, feeble-minded. Knowing the child possesses memories intensifies the ‘terms’ of this tacit agreement. The ones who walk away from “city Omelas” are those who can, the reader assumes, no longer rationalize or ignore. Never having been asked in the first place to be party to the terms (by dint of being born or otherwise naturalized citizens of the city), forced to accept the status of “receiver “of this city vision rather than its “producer,” some individuals choose not to go home after the viewing and “walk straight out of the city of Omelas, through the beautiful gates” for a place the narrator describes as “even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness.” Invoking the imagination is key here, arguably the one essential human capacity most at stake. Walking away is not met with objection; at least, conflict is conspicuously absent from the narrative, thus another inconvenient truth easily ignored by a population so adept at ignoring. The narrator continues, “I cannot describe [this other place] at all. It is possible that it does not exist.” Even though these walkers “seem to know where they are going,” across the farmlands and “towards the mountains,” they just “go on” and “walk ahead into the darkness” to somewhere that is at once nowhere.

This ‘somewhere’ is conveyed by the narrative’s contrasting details of setting, style, and narrative point of view, and best understood by what is absent. An unwalled and ungated polis home to the society of Odo introduces a city vision that privileges the lived experience of a population of receivers and their decendents. The “Festival of Summer” that opens and defines Omelas’ splendor posits cyclical, ritualized time against the-day-before-the-revolution’s less predictable, chaotic, historical time, enhanced by the title’s freezing of time in “the day before.”

This narrative is less scrutable, to say the least. Reading this story requires negotiating numerous foreign-sounding yet highly individualized names of people and places, details absent in Omelas, save the name of the city itself. Observations here are significantly filtered through the perspective of the elderly foundress’s post-stroke seventy-plus years of memories and experiences revealed on this day before. Laia’s waking and dying consciousness on this day fixate on never having known the name of the “tall weeds with dry, white, close-flowered heads” that “nodded above…swaying in the wind that always blew across the fields in the dusk.” Until the end of our days, there will always be more names to learn and names to be tried on, as Laia does “looking down at her [old lady] feet” observing: “Disgusting. Sad, depressing. Mean. Pitiful...Hideous: yes, that one too.” Contrast these words with the Omelan lexicon of “beauty,” “nobility,” “poignancy,” “profundity,” “victory,” and even “courage,” all of which are poignntly forgotten or defamiliarized in this narrative space.

An awareness of the fallibility of memory and the incompleteness of knowledge, an ignorance over ignoring, are symptomatic of a life spent occupied by the work of inventing (social and political) theories–specifically Asieo’s (Laia’s late husband’s) “theory of reciprocity” and Laia’s “principle of freedom of dress and sex”--and the disciplined mounting of a Movement. From Laia’s point of view and by the time the story takes place, these hard earned political theories have lost potency even if they were a positive outgrowth of her generation’s efforts to negotiate the terms of freedom for the utopia-receivers, for those who walked away from the Omelan vision which demanded, by contrast, plenty of structural ignoring and comparatively less structural ignorance, to employ Atwood’s apt qualification. Indeed, Omelas’ well-orchestrated festivals, honoring nobility, music, science, victory, and courage, contrast with Laias’ recognition that her mere survival as the oldest member of the Movement, her going on, and her dwelling within the confines of a repurposed bank building (one imagines those thick-walled stone structures) cum cooperative Odonian House (called unimaginatively “The Bank” and known as “the best...and oldest of all the cooperative Houses”) do not enoble in the classical sense. Surrounded and visited by youthful worshipers from near and far, Laia laments that they no longer have anything to learn from her, a sign of knowing’s decline.

Even to die, she subsequently comes to understand, “was merely to go on in another direction.” “What was the good working for freedom all your life and ending up without any freedom at all?” she asks in recognition of a lifetime spent in the metaphorical space of the day before. A troubling ignorance is also implied by several details: by her own having never learned the names of the tall weeds with flowers, by the Movement’s being “not strong on names” as reflected in its ever-shifting slogans, and by the younger generation’s open disinterest in learning, problematic when it comes to grand theories such as reciprocity and freedom subjected to time: “Favoritism, elitism, leader-worship, they crept back and cropped up everywhere,” Laia notes. The overwhelming result of this narrative’s brilliantly achieved point of view is the unnerving sense that every day is a day before the revolution.

A visit to the “noisy, stinking streets of stone, where she had grown up and lived all her life, except for the fifteen years in prison” brings back imaginings of the Movement’s original utopian vision:

There would not be slums like this, if the Revolution prevailed. But there would be misery. There would always be misery, waste, cruelty. She had never pretended to be changing the human condition, to be Mama taking tragedy away from the children so they wouldn’t hurt themselves. Anything but. So long as people were free to choose, if they choose to drink flybane and live in the sewers, it was their business. Just so long as it wasn’t the business of Business, the source of profit and the means of power for other people.

But that view occurred, she realizes, “before she knew anything…before she knew what ‘capital’ meant” and significantly “before she’d been farther than River Street” to see for herself firsthand that she “and the other kids, and her parents, and their parents, and the drunks and whores…were at the bottom of something…the foundation, the reality, the source.” The futility of an education, of intergenerational exchange and value, of walking away, looms large.

With the imaginative benefits of fiction, LeGuin reconstitutes these conflicts and sets up the opportunity for a comparative analysis that unearths the possibility that modern human history might well be understood a series of walking away from one utopian vision to another, or more specifically, from visions that privilege the freedom of the producers to those that privilege the freedom of the receiver, and seemingly back again, a going on. As Laia’s character meant to say in her earlier writing, words that were meant to help shape a next generation: “If you wanted to come home you had to keep going on…‘True journey is return.’” Late in the story after her escape to the streets, Laia confronts the reality of her own theory, “She had come home; she had never left home. ‘True voyage is return’.” Walking away is not merely a pendulum swinging, as coming home or the realization that one has never left home are not to be read as failure but rather as creative potential: utopias are everwhere and somewhere.

I appreciate the implicit notion that the function of utopianizing approaches a dialectic in the Hegelian sense. Utopias and their counterpart dystopias, the imagining of “cities” on hills or in valleys, are something humans ejected from a state of nature do and are thus worth scrutinizing. In response to the critics who accused her of “[dragging] civilization down into the mud,” Laia explained, “[I]f you were God you made [mud] into human beings, and if you were human you tried to make it into houses where human beings could live.” It is not hard to imagine these words flowing from the pen and civic activism of Jane Jacobs, who noted the failure of so many “houses” destroyed by too many attempts at remaking “human beings.” In other words, the utopia producers might forget they are not God, which is easy to do given certain prerequisites of the times (available and emerging technologies), place (sub/urban, temperate), and, indeed, politics (the polis, libertarian or anarchial, authoritarian or not). But, as Laia continues in defense of her fellow utopia receivers, “nobody who thought he was better than mud could understand.” It is worth noting that Laia is not only an elderly woman but also has skin “the color of mud.” The repetition of the word “mud” in the story, rife with artisanal connotation--Adam having emerged from God’s shaping of mud--calls the reader to interrogate the nexus of race, class, and gender in the imagining, shaping, and adapting of human beings and their houses.

Each utopian iteration, as suggested in this comparative reading, is a projection of a thesis that generates conflict (antithesis), and is reformulated as a synthesis (future design). The new idea, say, the embedded utopian vision of “The Day Before the Revolution,’’ contains a germ of the old, the Omelan. This observation is reinforced by the Day Before’s final images of Laia “[slipping] away unnoticed among the people busy with their planning and excitement”–it is, after all, the day before the revolution–and there is murmuring of “the general strike.” Whatever the Movement had hoped for seems to be coming to fruition, an inequality solved: The walkers’ freedom is centered, and a golden age lies ahead.

But not so fast. The planners are a small group of people in an Odonian House, a communal design concept for which “there were always more wanting to live in…than could be properly accommodated,” solid awarness for future architects called to draft blueprints for a population expected to receive. Laia is exhausted, as the reader has been made well aware throughout the eight dense pages of this short story, and decides to leave the gathering and walk alone upstairs to her large attic-level room. (She notes earlier that she does not share her room as others in the House do.) Resting on the landing she thinks, “Above, ahead, in her room, what awaited her? The private stroke.” Though the slip (stroke for strike) is received by her as “mildly funny,” the reality is less so: “She started up the second flight of stairs, one by one, one leg at a time, like a small child.” The simile recalls the suffering child of Omelas (also facing death) and the “terms” inherent perhaps in all utopianizing: the necessary negotiation of liberty and limit, and the “journey as return” motif (Sorkin, 2010, 9). In what way, the story seems to ask, might the image of the elderly foundress in the attic with skin the color of mud serve as the germ for the next city iteration, assuming the “revolution” takes place?

Bibliography

Davidson, J. P.L. (2019, June 1). My utopia is your utopia? William Morris, utopian theory and the claims of the past. Thesis Eleven, 152(1), 87-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513619852684

Gopnik, A. (2016). Jane Jacobs’s Street Smarts. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/26/jane-jacobs-street-smarts

Guiton, J. (1981). The Ideas of Le Corbusier on Architecture and Urban Planning. George Brazillier.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. course PDF.

Laurence, P. (2016, September 24). Jane Jacobs Was No “Saint,” “Great Man,” or “Ordinary Mom” — BECOMING JANE JACOBS. BECOMING JANE JACOBS. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from http://becomingjanejacobs.com/blog/2016/9/22/jane-jacobs-was-no-saint

LeCorbusier. (1967). The Radiant City. Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of Our Machine-Age Civilization. The Orion Press.

LeGuin, U. K. (1973). The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. PDF. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pNuJMoFjYYS9pMFiawj2oM09q2utYcdQ/view?usp=sharing

Le Guin, U. K. (1974). The Day Before the Revolution. The Anarchist Library. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ursula-k-le-guin-the-day-before-the-revolution

Reid, E. (2022, March 25). Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Margaret Atwood. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/25/podcasts/transcript-ezra-klein-interviews-margaret-atwood.html

Sorkin, M. (2010). Eutopia Now! Harvard Design Magazine, 31(Fall/Winter 2009/10), 6-21.

There are seasonal festivals–the story opens with the “Festival of Summer’’ among ”great parks and public buildings,” a “great water-meadow called the Green Fields,” processions, music, and “decorous” unnamed people of all ages in the streets. “[T]hese were not simple folk, not dulcet shepherds, noble savages,” the narrator explains, precisions that preempt any attempt to dismiss Omelas as one of those “bland utopias.”

The narrator’s evocation of a “you” and a “we” throughout the text distinguishes LeGuin’s Omelas as a utopia that might very well be attainable, even if it appears to be a sort of “miracle.” Furthermore, it is eerily familiar to those who have been raised in the late 20th-century American suburban dream. “Let me tell you about the people of Omelas,” the narrator announces, “They were not naive and happy children –though their children were, in fact, happy. They were mature, intelligent, passionate adults whose lives were not wretched.”

In Omelas, the narrator adds, “I think there would be no cars or helicopters in and above the streets,” which the reader might interpret in two ways: first, that the technology of mechanical, fossil-fueled movement is somehow a sinister or un-utopian addition to city living and thus gladly banished here, and, second, that there is little crime in this urban vision to necessitate surveillance or policing power “in and above the streets,” an image that continues to plague certain neighborhoods of contemporary American cities. And yet, remarkably, the citizens of Omelas, the narrator imagines, “could perfectly well have central heating, subway trains, washing machines, and all kinds of marvelous devices not yet invented…fuelless power, a cure for the common cold.” All manner of technology is available to this city’s producers as it is to ours--the story projects itself into the present.

The clincher for the citizens of Omelas, however, as it is metaphorically also in ours, is the discovery that all of this “splendor” comes at a cost. At some point in their education, “between eight and twelve, whenever they seem capable of understanding,” each citizen must learn “that [the child] has to be there…that [the citizens’] happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.” Since there is much to gain (as the words in bold suggest) by accepting the suffering child, there is also much to lose.

Any effort to save the child is immediately abandoned by an additional stipulation, that this “splendor of their lives” will disappear if anyone attempts to save the child, and so the citizens of Omelas live knowing “that they, like the child, are not free.” The return on such a utilitarian investment–accepting the suffering of one for the happiness of thousands–will demand a lifetime of ignoring a hard reality. As Margaret Atwood writes in her dystopian novel The Handmaid’s Tale, “Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance. You have to work at it” (Reid, 2022). In Omelas, ignoring (in other words, not walking away) is what “makes possible the nobility of their architecture, the poignancy of their music, the profundity of their science.” These are not lazy people, and so their work and dedication are rewarded with “a sense of victory…the celebration of courage…[a] boundless and generous contentment…and the victory they celebrate is that of life.” Ignorance absent ignoring might very well achieve architecture, music, and science but without the many desireable qualifiers. If there is freedom for the citizens, it is only freedom from, as the narrator notes: “One thing I know there is none of in Omelas is guilt.”

Though some citizens are “content merely to know [the child] is there,” others choose to visit the child, “who has not always lived in the tool room and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice”: he sits in his excrement, thin, belly protruding, feeble-minded. Knowing the child possesses memories intensifies the ‘terms’ of this tacit agreement. The ones who walk away from “city Omelas” are those who can, the reader assumes, no longer rationalize or ignore. Never having been asked in the first place to be party to the terms (by dint of being born or otherwise naturalized citizens of the city), forced to accept the status of “receiver “of this city vision rather than its “producer,” some individuals choose not to go home after the viewing and “walk straight out of the city of Omelas, through the beautiful gates” for a place the narrator describes as “even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness.” Invoking the imagination is key here, arguably the one essential human capacity most at stake. Walking away is not met with objection; at least, conflict is conspicuously absent from the narrative, thus another inconvenient truth easily ignored by a population so adept at ignoring. The narrator continues, “I cannot describe [this other place] at all. It is possible that it does not exist.” Even though these walkers “seem to know where they are going,” across the farmlands and “towards the mountains,” they just “go on” and “walk ahead into the darkness” to somewhere that is at once nowhere.

︎

“The Day Before the Revolution” picks up where “Omelas” leaves off as LeGuin’s introduction explains: “This story is about one of the ones who walked away from Omelas.” That one is the elderly Laia Asieo Odo, who has just suffered a stroke, the foundress of the society of Odonians and of Odonianism, which the author’s note explains is akin to the political theory of anarchism, whose “principal target is the authoritarian State (capitalist or socialist); its principal moral-practical theme is cooperation (solidarity, mutual aid).” This ‘somewhere’ is conveyed by the narrative’s contrasting details of setting, style, and narrative point of view, and best understood by what is absent. An unwalled and ungated polis home to the society of Odo introduces a city vision that privileges the lived experience of a population of receivers and their decendents. The “Festival of Summer” that opens and defines Omelas’ splendor posits cyclical, ritualized time against the-day-before-the-revolution’s less predictable, chaotic, historical time, enhanced by the title’s freezing of time in “the day before.”

This narrative is less scrutable, to say the least. Reading this story requires negotiating numerous foreign-sounding yet highly individualized names of people and places, details absent in Omelas, save the name of the city itself. Observations here are significantly filtered through the perspective of the elderly foundress’s post-stroke seventy-plus years of memories and experiences revealed on this day before. Laia’s waking and dying consciousness on this day fixate on never having known the name of the “tall weeds with dry, white, close-flowered heads” that “nodded above…swaying in the wind that always blew across the fields in the dusk.” Until the end of our days, there will always be more names to learn and names to be tried on, as Laia does “looking down at her [old lady] feet” observing: “Disgusting. Sad, depressing. Mean. Pitiful...Hideous: yes, that one too.” Contrast these words with the Omelan lexicon of “beauty,” “nobility,” “poignancy,” “profundity,” “victory,” and even “courage,” all of which are poignntly forgotten or defamiliarized in this narrative space.

An awareness of the fallibility of memory and the incompleteness of knowledge, an ignorance over ignoring, are symptomatic of a life spent occupied by the work of inventing (social and political) theories–specifically Asieo’s (Laia’s late husband’s) “theory of reciprocity” and Laia’s “principle of freedom of dress and sex”--and the disciplined mounting of a Movement. From Laia’s point of view and by the time the story takes place, these hard earned political theories have lost potency even if they were a positive outgrowth of her generation’s efforts to negotiate the terms of freedom for the utopia-receivers, for those who walked away from the Omelan vision which demanded, by contrast, plenty of structural ignoring and comparatively less structural ignorance, to employ Atwood’s apt qualification. Indeed, Omelas’ well-orchestrated festivals, honoring nobility, music, science, victory, and courage, contrast with Laias’ recognition that her mere survival as the oldest member of the Movement, her going on, and her dwelling within the confines of a repurposed bank building (one imagines those thick-walled stone structures) cum cooperative Odonian House (called unimaginatively “The Bank” and known as “the best...and oldest of all the cooperative Houses”) do not enoble in the classical sense. Surrounded and visited by youthful worshipers from near and far, Laia laments that they no longer have anything to learn from her, a sign of knowing’s decline.

Even to die, she subsequently comes to understand, “was merely to go on in another direction.” “What was the good working for freedom all your life and ending up without any freedom at all?” she asks in recognition of a lifetime spent in the metaphorical space of the day before. A troubling ignorance is also implied by several details: by her own having never learned the names of the tall weeds with flowers, by the Movement’s being “not strong on names” as reflected in its ever-shifting slogans, and by the younger generation’s open disinterest in learning, problematic when it comes to grand theories such as reciprocity and freedom subjected to time: “Favoritism, elitism, leader-worship, they crept back and cropped up everywhere,” Laia notes. The overwhelming result of this narrative’s brilliantly achieved point of view is the unnerving sense that every day is a day before the revolution.

A visit to the “noisy, stinking streets of stone, where she had grown up and lived all her life, except for the fifteen years in prison” brings back imaginings of the Movement’s original utopian vision:

There would not be slums like this, if the Revolution prevailed. But there would be misery. There would always be misery, waste, cruelty. She had never pretended to be changing the human condition, to be Mama taking tragedy away from the children so they wouldn’t hurt themselves. Anything but. So long as people were free to choose, if they choose to drink flybane and live in the sewers, it was their business. Just so long as it wasn’t the business of Business, the source of profit and the means of power for other people.

But that view occurred, she realizes, “before she knew anything…before she knew what ‘capital’ meant” and significantly “before she’d been farther than River Street” to see for herself firsthand that she “and the other kids, and her parents, and their parents, and the drunks and whores…were at the bottom of something…the foundation, the reality, the source.” The futility of an education, of intergenerational exchange and value, of walking away, looms large.

︎

Some decades into the real-world utopian visions and blueprints designed to address “perceptions of the enormous problems of existing cities” (Guiton, 1981, 93) and thus effect social reform such as those proposed by LeCorbusier in his Ville Radieuse (1930) and later responses to them such as those in Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), LeGuin’s stories (published in the early 70s) gain historical dimension and relevance, a framework even. The figure of Laia in the streets, who has been reduced to a “phenomenon, a monument… everybody’s grandma” recalls Jacobs’ pioneering streetwalker point of view and her work’s essentializing critics such as Lewis Mumford, who titled his New Yorker review of Jacobs’ influential Death and Life “Mother Jacobs’ Home Remedies” (Gopnik, 2016). Nonetheless, not too long ago, on Bleecker Street, I recall seeing signs in shop windows with the slogan “More Jane Jacobs, Less Marc Jacobs” in response to continued gentrification and commercialization of the West Village, a campaign designed to check what Laia critiques as “the power of profit” and the relations that power shapes. With the imaginative benefits of fiction, LeGuin reconstitutes these conflicts and sets up the opportunity for a comparative analysis that unearths the possibility that modern human history might well be understood a series of walking away from one utopian vision to another, or more specifically, from visions that privilege the freedom of the producers to those that privilege the freedom of the receiver, and seemingly back again, a going on. As Laia’s character meant to say in her earlier writing, words that were meant to help shape a next generation: “If you wanted to come home you had to keep going on…‘True journey is return.’” Late in the story after her escape to the streets, Laia confronts the reality of her own theory, “She had come home; she had never left home. ‘True voyage is return’.” Walking away is not merely a pendulum swinging, as coming home or the realization that one has never left home are not to be read as failure but rather as creative potential: utopias are everwhere and somewhere.

I appreciate the implicit notion that the function of utopianizing approaches a dialectic in the Hegelian sense. Utopias and their counterpart dystopias, the imagining of “cities” on hills or in valleys, are something humans ejected from a state of nature do and are thus worth scrutinizing. In response to the critics who accused her of “[dragging] civilization down into the mud,” Laia explained, “[I]f you were God you made [mud] into human beings, and if you were human you tried to make it into houses where human beings could live.” It is not hard to imagine these words flowing from the pen and civic activism of Jane Jacobs, who noted the failure of so many “houses” destroyed by too many attempts at remaking “human beings.” In other words, the utopia producers might forget they are not God, which is easy to do given certain prerequisites of the times (available and emerging technologies), place (sub/urban, temperate), and, indeed, politics (the polis, libertarian or anarchial, authoritarian or not). But, as Laia continues in defense of her fellow utopia receivers, “nobody who thought he was better than mud could understand.” It is worth noting that Laia is not only an elderly woman but also has skin “the color of mud.” The repetition of the word “mud” in the story, rife with artisanal connotation--Adam having emerged from God’s shaping of mud--calls the reader to interrogate the nexus of race, class, and gender in the imagining, shaping, and adapting of human beings and their houses.

Each utopian iteration, as suggested in this comparative reading, is a projection of a thesis that generates conflict (antithesis), and is reformulated as a synthesis (future design). The new idea, say, the embedded utopian vision of “The Day Before the Revolution,’’ contains a germ of the old, the Omelan. This observation is reinforced by the Day Before’s final images of Laia “[slipping] away unnoticed among the people busy with their planning and excitement”–it is, after all, the day before the revolution–and there is murmuring of “the general strike.” Whatever the Movement had hoped for seems to be coming to fruition, an inequality solved: The walkers’ freedom is centered, and a golden age lies ahead.

But not so fast. The planners are a small group of people in an Odonian House, a communal design concept for which “there were always more wanting to live in…than could be properly accommodated,” solid awarness for future architects called to draft blueprints for a population expected to receive. Laia is exhausted, as the reader has been made well aware throughout the eight dense pages of this short story, and decides to leave the gathering and walk alone upstairs to her large attic-level room. (She notes earlier that she does not share her room as others in the House do.) Resting on the landing she thinks, “Above, ahead, in her room, what awaited her? The private stroke.” Though the slip (stroke for strike) is received by her as “mildly funny,” the reality is less so: “She started up the second flight of stairs, one by one, one leg at a time, like a small child.” The simile recalls the suffering child of Omelas (also facing death) and the “terms” inherent perhaps in all utopianizing: the necessary negotiation of liberty and limit, and the “journey as return” motif (Sorkin, 2010, 9). In what way, the story seems to ask, might the image of the elderly foundress in the attic with skin the color of mud serve as the germ for the next city iteration, assuming the “revolution” takes place?

Bibliography

Davidson, J. P.L. (2019, June 1). My utopia is your utopia? William Morris, utopian theory and the claims of the past. Thesis Eleven, 152(1), 87-101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513619852684

Gopnik, A. (2016). Jane Jacobs’s Street Smarts. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/09/26/jane-jacobs-street-smarts

Guiton, J. (1981). The Ideas of Le Corbusier on Architecture and Urban Planning. George Brazillier.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. course PDF.

Laurence, P. (2016, September 24). Jane Jacobs Was No “Saint,” “Great Man,” or “Ordinary Mom” — BECOMING JANE JACOBS. BECOMING JANE JACOBS. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from http://becomingjanejacobs.com/blog/2016/9/22/jane-jacobs-was-no-saint

LeCorbusier. (1967). The Radiant City. Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of Our Machine-Age Civilization. The Orion Press.

LeGuin, U. K. (1973). The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas. PDF. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pNuJMoFjYYS9pMFiawj2oM09q2utYcdQ/view?usp=sharing

Le Guin, U. K. (1974). The Day Before the Revolution. The Anarchist Library. Retrieved April 6, 2022, from https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ursula-k-le-guin-the-day-before-the-revolution

Reid, E. (2022, March 25). Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Margaret Atwood. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/25/podcasts/transcript-ezra-klein-interviews-margaret-atwood.html

Sorkin, M. (2010). Eutopia Now! Harvard Design Magazine, 31(Fall/Winter 2009/10), 6-21.

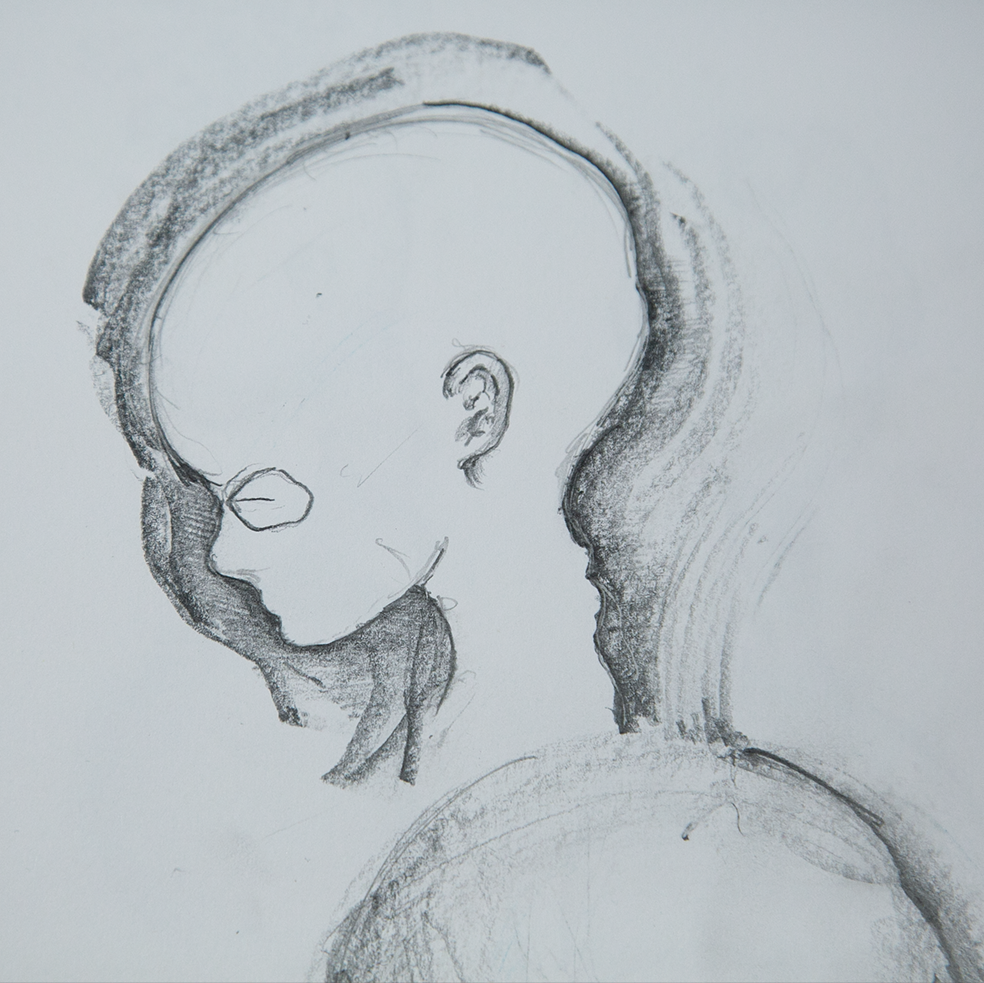

Sketches and resulting forms (above) were fashioned in response to the hauntng image of the child that matched my memory reading “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” and were submitted for an early “design principles” studio project (Fall 2019). Having the opportunity to return to the story and discover its sequel in “The Day Before the Revolution” for this essay proved a highlight of my concluding undergraduate experience.